With new honors falling like autumn leaves, Riccardo Muti reflects on the conductor’s art

In Part 2 of a Chicago On the Aisle interview, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s music director extols Italian training, calls Toscanini his idol and admits impatience with routine effort – and prima donnas.

In Part 2 of a Chicago On the Aisle interview, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s music director extols Italian training, calls Toscanini his idol and admits impatience with routine effort – and prima donnas.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

If conductor Riccardo Muti were a star baseball player, they’d be calling him Mr. October. Talk about a clean-up hitter: This month alone, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s music director will add to his wall of awards the title of Honorary Director for Life at the Rome Opera (announced Tuesday), the Birgit Nilsson Prize for lifetime achievement (which he received Thursday in Stockholm) and Spain’s Prince of Asturias Prize for lifetime achievement (which he will receive Oct. 21 in Oviedo).

“I don’t think if you receive a prize, you should think you are better,” Muti said quietly in a recent conversation, responding to congratulations on the Nilsson and Asturias honors. “It’s just a recognition that comes to you. Especially when you have not done anything to receive the prize.”

Nothing and everything. Muti is a musician’s musician, a philosophical artist and throughout his professional life a standard bearer for excellence in the opera house and concert hall. At age 70, he is one of the great conductors of the last half-century.

“I’m a musician not because my parents wanted one of their five sons to be a little genius that tomorrow will be the famous artist,” he said. “Many times families create these little monsters who sometimes become great artists. I am a musician thanks to the gentleman in that picture.” He points toward a framed sepia photo on the wall next to his desk at Symphony Center. “You recognize (Arturo) Toscanini. The young man with him is Nino Rota.”

“I’m a musician not because my parents wanted one of their five sons to be a little genius that tomorrow will be the famous artist,” he said. “Many times families create these little monsters who sometimes become great artists. I am a musician thanks to the gentleman in that picture.” He points toward a framed sepia photo on the wall next to his desk at Symphony Center. “You recognize (Arturo) Toscanini. The young man with him is Nino Rota.”

Muti, born in Naples, studied composition with Rota at the Conservatorio di musica “Giuseppe Verdi” in Milan, where his instructors also included composer Bruno Bettinelli and conductor Antonino Votto. But it was Rota whom Muti regarded as his true mentor.

The other man in that treasured photo would become the young conductor’s exemplar.

“Toscanini is my idol,” Muti said. “But idol is wrong. He is most representative of the Italian school.”

Asked to explain that more circumspect characterization, Muti launches into an appreciation of his celebrated forebear that steadily points back round to his first word: idol.

“There is an Italian way of making music,” he said. “First, the Italian school of conducting is based in the general study of music. But in other places, especially in this country, conducting is something you study in the books. When I ask young conductors, ‘Are you studying composition, do you play well the piano, do you know the violin?’ their answers are always vague.” He pauses and smiles faintly. “Toscanini came from the Italian school where you could study conducting only after seven years of composition, four years of harmony, three years of counterpoint, three years of orchestration.”

As a young man, Toscanini played cello at La Scala. Muti points out that Toscanini was in the pit when Verdi conducted “Otello” there.

“So-called specialists talk about how the Verdi sound should be this way or that way. Toscanini tells us exactly the sound Verdi wanted,” Muti said. “And nobody taught Toscanini how to move the arms. Nobody taught Furtwangler or Mahler or Mr. Thomas,” he adds, gesturing toward another photo on the wall, of CSO founding conductor Theodore Thomas.

“Today, it’s becoming a kind of mathematics. My teacher Antonino Votto was first assistant to Toscanini. He liked to quote Toscanini: ‘The arms are supposed to be the extension of your mind.’ Today, the tendency is for the arms to be something to show to the public. You have to look beautiful, jump around, because we are becoming a visual society, not a society that listens. Movies and television have done this.”

“Today, it’s becoming a kind of mathematics. My teacher Antonino Votto was first assistant to Toscanini. He liked to quote Toscanini: ‘The arms are supposed to be the extension of your mind.’ Today, the tendency is for the arms to be something to show to the public. You have to look beautiful, jump around, because we are becoming a visual society, not a society that listens. Movies and television have done this.”

Muti describes two key elements in the “Italian way” of conducting: a clear sense of structure and a melodic line that comes from opera.

“Not only the melody must sing – all the parts have to sing,” he said. “Toscanini would keep telling his musicians, ‘Canta, canta!’ Even the pizzicato should sing. In Bellini or Donizetti, even the accompaniment. You often hear this music played in the most lazy and unmusical way. German conductors are much more interested in the mass of a piece, and generally less interested in this (cantilena).”

Muti also makes a distinction between interpretation and putting oneself “in the composition with the composer.” The objective is always to serve the composer’s intentions, the conductor said.

“Toscanini was sometimes accused of being too objective or too cold, but my teacher (Votto) said his ‘Boheme’ was the performance Puccini loved most,” Muti said. “It was completely different from the way ‘Boheme’ is done today. It was not an opera full of tears where the tenor stays three hours on one note and the soprano does such and such, and it becomes cheap. Of course it moves people and makes them cry, but Puccini was a much more solid composer than that.”

And yet when asked if there are works in any genre that Muti would be just as happy to leave on the shelf for a while, he comes right back to opera – and Puccini.

“There are some operas I will never conduct,” he said. “One is ‘Butterfly,’ another is ‘Carmen.’ Not because I don’t like these operas but because there are too many others that are more interesting to me. You can spend your time better. At La Scala, I conducted 49 or 50 different operas, so I conduct many things. But take Gluck. After such music, you understand all the world after him.”

Berlioz agreed with that assessment, as did Mahler. But we’ve just blown past “Madama Butterfly,” which some would argue stands in the first rank of works for the opera stage.

“I doubt that ‘Butterfly’ is a masterpiece,” Muti said. “It’s a very nice opera, very beautiful, but ‘Tu, tu piccolo iddio?” he recites with a rising question mark in his voice as he quotes the geisha’s famous farewell to her child before killing herself. “And there are more important things for your soul than ‘Un bel di, vedremo levarsi un fil di fumo sull’estremo confin del mare,’” he quotes at solemn length with a palpable note of sarcasm – in his eyes.

“But when you do ‘Alceste’ of Gluck, then you really are on Olympus, no?”

Chicago Symphony audiences, treated last season to Muti’s concert presentation of Verdi’s “Otello,” can expect more opera in his programming mix. One of the world’s most distinguished opera conductors says that henceforth the only places to hear him do opera will be the Rome Opera, where he has a close association, and Chicago.

“I don’t want to do operas in other theaters because it’s too much time and also I want work with orchestras in places where I know my musicians,” he said. “The ‘Otello’ we did last year maybe helped to make people understand that opera is not about the tenor or the soprano, but it’s about the composer, and we all work in that direction.

“That’s the reason I’m an enemy of superstars, of ‘the voice.’ With me, nobody has been able to play the part of the prima donna, even when I was very young. Today, there’s a tendency to make operas showpieces for prima donnas because the conductors are becoming too weak and the directors are becoming too strong. In Roma and Chicago I will insist on a more authentic view, as I did in La Scala where I brought back ‘Traviata’ after 26 years of absence.”

He also restored two other middle-period Verdi masterpieces, “Rigoletto’ after a 22-year hiatus and ‘Il Trovatore’ after 23 years.

They were gone so long, Muti said, “because everybody was afraid. The public there is very strange. It’s Callas, Callas. But I brought those operas back in their original versions, without all the high notes. That’s something I’m very proud of.” And his face lights up like an exclamation mark.

Muti has a ready, if dry, sense of humor. But he is an intensely serious artist and musician.

“My first enemy is routine,” he said. “I don’t mind when there is a mistake in the orchestra. What I hate is indifference. That can make me furious. That is an insult to art, to music, to the public, and to me that is inconceivable. Our profession is to convey feelings. If you don’t have anything to say as a musician, you are in the wrong profession.”

At the end of a long, meandering conversation, Muti flashes a wide grin and takes off on a new tangent unprompted:

“When I go to the other world and I meet the composers, I will be happy to see Mozart, to see Wagner. The one composer I will be afraid to meet is Verdi. I dedicated my life to this composer. If he tells me, ‘You didn’t understand anything of what I wrote,’ then I will die for the second time.”

Related links:

- Part 1 of the interview: Riccardo Muti sidesteps Mahler for Bruckner

- More about Riccardo Muti: Visit his website

- Muti’s next concerts with the CSO: Orff’s “Carmina Burana”

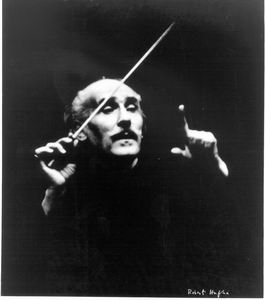

Photo captions and credits: Home page, top and middle: Riccardo Muti conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Photos by Todd Rosenberg). Bottom: Conductor Arturo Toscanini, Muti’s compatriot and idol.

Tags: Arturo Toscanini, Birgit Nilsson Prize, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Giuseppe Verdi, Nino Rota, Prince of Asturias Prize, Riccardo Muti, Rome Opera

No Comment »

6 Pingbacks »

[…] Chicago On the Aisle interviews Muti, Part 2: Reflecting on the conductor’s art […]

[…] Chicago On the Aisle interviews Muti, Part 2: Reflecting on the conductor’s art […]

[…] On the Aisle’s interview with Muti: Part 2 Photo captions and credits: Chicago Symphony and choral forces perform “Carmina […]

[…] On the Aisle’s interview with Muti: Part 2 Photo captions and credits: Chicago Symphony and choral forces perform “Carmina […]

[…] Riccardo Muti’s exclusive interview with Chicago On the Aisle: Read Part 2 […]

[…] Riccardo Muti’s exclusive interview with Chicago On the Aisle: Read Part 2 […]